“Watch me.”

If you’ve ever been around Farzad Mahmoudpour on the field, you’ve seen him jumping into drills and demonstrating every activity. He does it with precision and attention to detail — showing his players exactly what’s expected of them.

For him, showing is the ultimate form of coaching.

“Observation is the best thing,” he said — both of coaching others and of learning the game himself. With English as his second language, he finds it much easier to teach by example than use lengthy explanations.

“I understand that sometimes when I talk less, it’s better. I don’t mind, I accept it. But I know that if I show, I’m going to be one of the best. I trust myself.”

His talent as a player throughout his career has made showing a simple task.

Growing up in the Iranian city of Ghaemshahr, his street was full of family members, neighbors, and friends that helped him grow his love for the game. He was nicknamed Kela — a name still used decades later.

His first memories of soccer started in the streets where he played with kids of all ages. Watching the others helped him learn and develop as a player.

“On the street we played soccer every day,” he said. “And it was ordered by the ages — the older kids had the privilege to play first. When they got tired, the middle-aged kids go. When they got tired, then we go. But I was lucky, honestly because everybody saw that I was good. They’d say, ‘Ok, Kela, you can play with us.’ So I had the privilege to play with the older kids.”

He was a rising star on the pitch, even placing third in the national states competition. He was also verbally invited to a camp with the Iranian national team. But in 1979, a political revolution changed the course of his career.

In 1982 he was arrested as a dissident and jailed for advocating for political freedom. He was only 15 at the time.

But even in jail, soccer was his solace. He would organize mini tournaments during the prisoners’ one hour of daily fresh air time. He even convinced the older inmates to play.

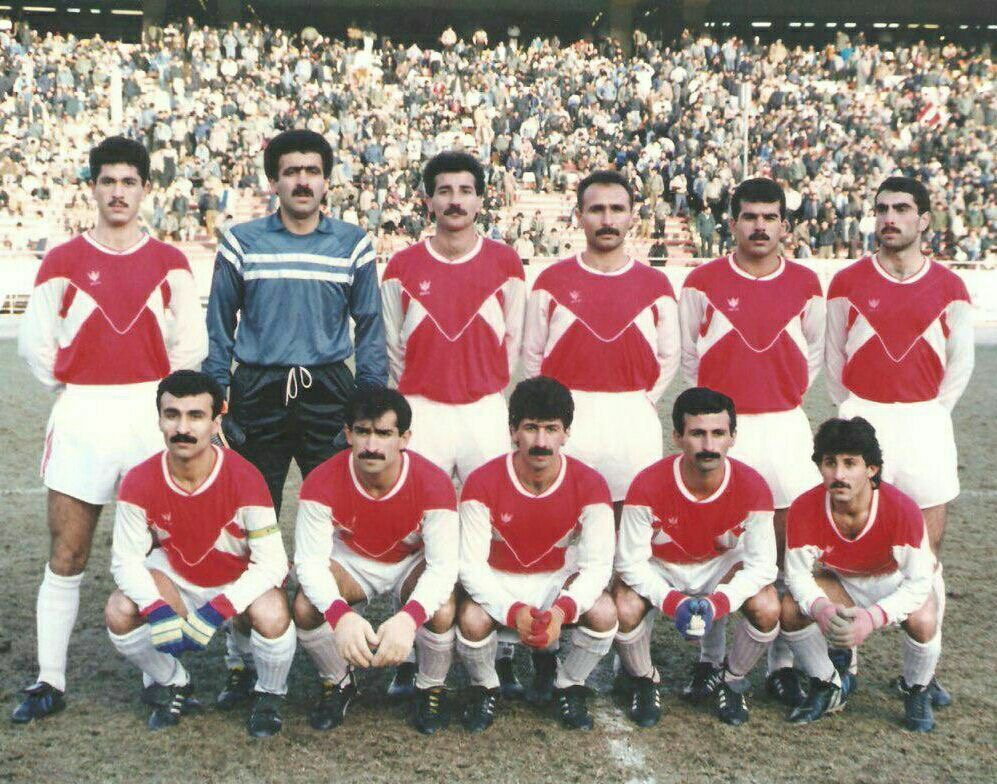

Imprisonment unfortunately meant that Farzad had to forego his national team and educational opportunities. After his release, though, he was able to secure a professional contract with a club called Nassaji where he made his debut at 18 years old.

His professional career in Iran was exciting – the 40,000 person stadium was full of devoted fans from around the entire city. He became a local celebrity, often getting playing advice (wanted or otherwise) from people in the community he saw throughout the day.

Farzad Mahmoudpour first played professionally with Nassaji at 18 years old.

Though his career was taking off, the political turmoil in Iran forced him and his family to flee the country in 1995. After a risky escape to Pakistan, Farzad, his wife, and his 2 year-old daughter tried their best to safely assimilate into a new culture. Soccer again became his touch point.

Through some connections with other Iranian and Afghani refugees, he started coaching and playing with a group called Hijrat Shah FC. They played throughout the area, dominating other teams and claiming local fame.

Again, soccer was his way to connect with his community. He often credits the sport for rescuing him and pushing him forward through adversity.

After many years of waiting, Farzad and his family were finally able to emigrate in 1998 to Chelsea, Massachusetts, right outside Boston. There they began taking English courses at the local community college and working to start their new life overseas.

“The social worker asked me,’What skills do you have?’” he explained. “I told her I was a soccer player.”

He began working odd jobs, but always saw soccer as his passion. On the side he trained and eventually tried out for the Boston Bulldogs and Cape Cod Crusaders — both being USL teams in the area. At the age of 34, he fought his way onto the Crusaders roster.

He began his coaching path the following year, traveling to Florida to pursue his NSCAA National License. Though he felt out of place and struggled to understand the course taught in English, his instructor encouraged him to simply “show him” that he understood the concepts — demonstrate the activities and coaching points, drag players around to show positioning, anything to help them understand what he’s asking for.

He did, and was awarded the license.

His coaching career really took off when he moved from Boston to the NOVA area. Players from his old Pakistani team had emigrated there, and encouraged him to join them. He did, coaching them throughout the year and starting his youth career in Arlington.

Soon after, he was awarded Coach of the Year from Arlington. Later, he began coaching within the state ODP program and at local high schools. He continued his licensure and received his USSF Youth National and “C” License.

He joined McLean in 2005 and has coached players in all age groups. Currently, he works with 04 and 07 girls and U9 boys. Even with his extensive experience, he still sees his coaching as a work in progress.

“To me the difference between coaching and playing: coaching is very hard. When I go to the field, I feel like I’m a student. I’m focused, I’m teaching but I’m learning. Sometimes I feel like I don’t know anything about this game, you know?”

But observation is still the key to Farzad’s success. His ability to see the game and understand his players using his own experiences means he’s able to connect on a deeper level.

“The advantage I have is when I see something that is connected to my playing so I can put myself in my player’s shoes — physically, mentally, technically. When a player is tired, I feel it. When a player is rolling their eyes, I can feel it. As soon as they move, I try to feel it.”

Farzad’s goal is to continue working with and developing the younger age groups. Their ability to learn quickly and develop key skills draws him in as a coach.

Still, you’ll likely see him jumping into sessions — regardless of their age. He also often plays pickup in over-50 leagues and with other Iranian teams. His passion for the game hasn’t faltered.

Farzad still plays in adult leagues, even competing in national tournaments.

Coach Farzad often participates in his players’ training sessions.

“Playing is a meditation for me,” he said.

To Farzad, soccer is so much more than a fun game. It has taught him discipline, given him joy in dark moments, and helped him meet amazing people. It’s his connection to his community back home, and a way for him to remember those who he left behind in Iran.

He hopes to one day return to his home there. His community means the world to him and modern technology has helped him stay connected.

But for now, he will continue to do amazing things in the American soccer community. It’s clear his passion for the game isn’t letting up any time soon.

So next time you see Coach Farzad on the field, ask him to show you a thing or two.